10. Individual Security in a Stateless Society

- A nonstate system of justice

- Is it anarchy?

- Conflict between protectors

- Protection for criminals

- Justice for sale

- Security for the poor

- The quality of protection

- Organized crime

- Protection or extortion?

- Monopolization

- Collusion and cartelization

- The traditional problem for cartels

- Cartelization by threat of force

- Cartelization through denial of

extended protection - HOA versus government

- Conclusion

10.1 A nonstate system of justice

10.1.1 Protection agencies

In any realistic human society, even an anarchist one, at least some individuals will commit aggression against others. The inhabitants of the anarchic society would most likely wish to develop systematic institutions for the provision of security, including a collection of protection agencies or security companies whose function would be to protect individuals from aggression against their persons and property and to apprehend aggressors after the fact.[1] These agencies, in brief, would serve the function that police serve in governmental systems.

In the absence of government, protection agencies would arise for the same reason that most businesses arise in a free market; namely, that there is a need which people are willing to pay to have satisfied. The agencies would charge money for their services, just as private security companies presently charge for their services.

Who would pay the security agencies? Individuals might hire their own security company, or neighborhood homeowners' associations might hire security for their neighborhoods, or owners of apartment buildings or businesses might hire security for their buildings, or some combination of these might occur.

Why does the anarchist not stipulate the details of nonstate security arrangements? Because the functioning of the system is determined by the individuals occupying it; therefore, the answers to questions about how the system would work must take the form of speculative predictions rather than stipulations (the same is true of any untried institution, though this fact is little recognized). The details of security arrangements would be determined by market forces and individual choices. If, for example, customers strongly preferred to patronize businesses that provided their own security, then most businesses would hire their own security.

What services would protection agencies provide? This, too, would depend upon customer demand. In some cases, they might provide armed patrols. In other cases, they might provide security cameras and alarm systems. After a crime was committed, they might provide detectives and armed 'police' to apprehend the criminals. Once apprehended, the criminals would be compelled to pay compensation for their crimes.

What would protection agencies do in the event that an accused criminal maintained his innocence? In that case, some institution serving the function of a court system would be needed.

10.1.2 Arbitration firms

In an anarchic society, just as in government-based societies, people would sometimes have disputes. One important kind of dispute occurs when a person is accused of a crime which he denies committing. Another type occurs when people disagree over whether a particular type of conduct ought to be tolerated; for instance, I may think my neighbor is playing his music too loud, while he thinks the volume is just fine. A third type concerns the terms of business relationships, including disputes about the interpretation of contracts. In each of these cases, the disagreeing parties need an institution functioning like a court to resolve their dispute.

In the absence of a state, this need would be supplied by private arbitration firms. Arbitration by a neutral third party is the best way to resolve most disputes, since it generally provides a good chance of delivering a reasonably fair resolution, and the costs of achieving this resolution are almost always far less for both parties than the costs of attempting a resolution through violence. For these reasons, almost all individuals would want their disputes to be resolved through arbitration.

Who would hire the arbitrators? Perhaps the parties to a dispute would agree on an arbitrator and split the cost between them. Or perhaps their security agencies would select the arbitrator. Suppose Jon accuses Sally of stealing his cat. He informs his security agency of the theft and asks them to retrieve the cat. But Sally notifies her security agency that Jon is attempting to steal her cat and asks them to defend the cat. If Jon and Sally patronize the same security agency, this agency may hire an arbitration company to determine to whom the cat belongs, so that the agency may decide whose claim to enforce. If Jon and Sally patronize different agencies, the two agencies will jointly select an arbitration company, with the understanding that both will accept the verdict of the arbitrator.

These are the basic institutions of a well-ordered anarchist society. In such a society, the most fundamental functions commonly ascribed to the state are not eliminated but privatized. A great many questions naturally arise about such a system.

In the remainder of this chapter, I address the most important questions about private protection agencies. Questions concerning arbitration firms will be taken up in the following chapter.

10.2 Is it anarchy?

The system just sketched is commonly referred to as 'anarcho-capitalism', 'free market anarchism', or 'libertarian anarchism'. One might ask, however, whether the system truly qualifies as a form of anarchy rather than, say, a system of competing governments.[2]

Semantic questions about the use of 'government' and 'anarchy' are of no great importance. However, the system differs in two crucial respects from all presently existing governmental systems, and it is these differences that lead me to call the system a form of anarchy.

The first difference is one of voluntariness versus coerciveness. Governments force everyone to accept their services; as we have seen (Chapter 2 and 3), the social contract is a myth. Protection agencies, by contrast, are chosen by customers, who make actual, literal contracts with them.

The second difference is one of competition versus monopoly. Governments hold geographical monopolies on protection and dispute-resolution services,[3] and changing one's government tends to be very difficult and costly, so governments feel little competitive pressure. In the anarchist system, protection agencies and arbitration companies are in constant competition with each other. If one were dissatisfied with one's protection agency, one could switch to another agency at little cost without moving to another country.

These two differences are the fundamental source of all the advantages claimed for anarcho-capitalism over traditional government. The voluntariness of the anarcho-capitalist scheme makes it more just than a coercive system, and both traits make the anarcho-capitalist system less abusive and more responsive to people's needs than coercive, monopolistic systems.

10.3 Conflict between protectors

Competing security agencies might seem to have significant motives for direct physical confrontation with one another. Since they are in direct economic competition, one agency might wish to attack another in the hopes of putting the other agency out of business. Or in the event of a dispute between customers of different agencies, security agencies might go to war to defend their respective clients' interests rather than allowing the dispute to be resolved by arbitration. For these reasons, some argue that an anarchist society would be riven with interagency wars.[4]

10.3.1 The costs of violence

As discussed earlier (Section 9.2), violent conflict tends to be very dangerous for both parties; rational individuals therefore seek to avoid provoking such conflicts and prefer peaceful methods of dispute resolution, such as third-party arbitration, whenever available.

But in spite of the prudential and moral arguments against engaging in avoidable violent confrontations, such confrontations periodically break out among ordinary individuals. Why does this occur? In essence, the reason is that in the general population, there are a wide variety of attitudes and motivations, and among all this variety there are some individuals with unusually high degrees of physical confidence, unusually low concern for their own physical safety, and unusually low capacity for impulse control - a collection of traits often referred to as 'recklessness'.[5]

Business managers, however, are considerably more uniform than the general population. They tend to share two traits in particular: a strong desire to generate profits for their businesses, and a reasonable awareness of the effective means of doing so. Individuals who lack these traits are unlikely to emerge at the head of a business, and if they do, the market is likely either to remove them from that position (as where a company's board of directors replaces its CEO) or to remove the company from the marketplace (as in bankruptcy). Thus, business managers are even less likely to behave in clearly profit-destroying ways than ordinary individuals are to behave in ways that clearly endanger their own physical safety.

But war is, putting it mildly, expensive. If a pair of agencies go to war with one another, both agencies, including the one that ultimately emerges the victor, will most likely suffer enormous damage to their property and their employees. It is highly improbable that a dispute between two clients would be worth this kind of expense. If at the same time there are other agencies in the region that have not been involved in any wars, the latter agencies will have a powerful economic advantage. In a competitive marketplace, agencies that find peaceful methods of resolving disputes will outperform those that fight unnecessary battles. Because this is easily predictable, each agency should be willing to resolve any dispute peacefully, provided that the other party is likewise willing.

10.3.2 Opposition to murder

Employees of a security agency have their own individual wills, distinct from the goals of the agency. If management decided to attack another agency solely to put a competitor out of business, widespread desertion is the most probable result. There are two reasons for this. First, most human beings are opposed to undertaking very large risks to their own lives for the sake of maximizing profits for their boss. Combat with another security agency would be much more dangerous than the normal work of apprehending common criminals, since the other agency would be better armed, organized, and trained than typical criminals.

Second, most people in contemporary societies are strongly opposed to murdering other members of their society.[6] This 'problem' has long been recognized by military experts whose concern is convincing soldiers to kill as many of the enemy as possible. On the basis of interviews with World War II soldiers, General S. L. A. Marshall famously concluded that no more than one-quarter of American soldiers actually fired their weapons in a typical battle.[7] Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman relates numerous cases in which the casualty rate during a battle was far lower than could plausibly be reconciled with the assumption of a genuine effort by each side to kill the other. In one striking incident, a Nicaraguan Contra unit was ordered by its commander to massacre the passengers on a civilian river launch. When the time came to open fire, every bullet miraculously sailed over the heads of the civilians. As one soldier explained, 'Nicaraguan peasants are mean bastards, and tough soldiers. But they're not murderers.'[8]

This is not to deny that some human beings are murderers; it is only to say that the overwhelming majority of human beings are strongly opposed to murder. A small percentage of people are willing to murder; however, these individuals are not generally desirable employees, and thus it is unlikely that a protection agency would wish to staff itself with such people.

What about the finding of the Milgram experiment (Section 6.2), in which people proved willing to electrocute a helpless victim when so ordered by a scientist? The fear of defying authority can overcome people's resistance to murder. Though business managers have much less of an aura of authority than government officials, might a security agency manager nevertheless be able to exploit this flaw in human nature to induce employees to kill members of rival agencies?

Perhaps one could, though it is worth noting a few other features of Milgram's experiment. First, the gradual escalation of the experimenter's demands, starting from a seemingly legitimate scientific experiment, was a crucial feature of the design. If Stanley Milgram had simply handed a pistol to his subjects as they walked in the door and told them to shoot another subject, he would not have succeeded. But perhaps a clever security agency manager, versed in psychology, could similarly manipulate circumstances.

Second, Milgram's subjects were not in any personal danger from the person they were supposedly electrocuting. If the 'learner' in the experiment had the ability to shock the teacher back, it is doubtful how far the teacher would have continued with the experiment. A warlike company manager would need to convince employees not only to murder but to risk being killed in turn.

Third, though most of Milgram's subjects obeyed, they did so with great reluctance, exhibiting signs of extreme stress. Even if a warlike agency managed to get employees to commit murder, the employees would be extremely unhappy, and the agency would probably soon lose most of its employees. During the 1960s, American war protesters displayed posters and bumper stickers with the slogan, 'What if they gave a war and nobody came?'[9] In the unlikely event that a protection agency declared war against another agency, residents of the anarchist society might finally have the chance to observe the answer to this question.

10.3.3 Conflict between governments

We have just seen why war between security agencies is unlikely. If, on the other hand, we rely upon government for our protection, is there any account of why war between states would be unlikely? A statist might offer two reasons for considering interstate war a smaller threat than interagency war:

- Since governments possess territorial monopolies, citizens of different states come into conflict less often than the customers of different protection agencies would.

- There is less competition among governments than there is among protection agencies. The large costs of moving from one country to another, including the barriers that governments themselves often place in the way, enable a government to extract monopoly profits from its populace with little fear of losing 'customers' to a rival government. Therefore, a government has less cause to wish to eliminate rival governments than a protection agency has to wish to eliminate rival agencies.

These are valid considerations. On the other hand, there seem to be several reasons for expecting the problem of intergovernmental warfare to be more serious than that of interagency warfare:

- Business leaders tend to be driven chiefly by the profit motive. Government leaders are more likely to be driven by ideology or the desire for power. Because of the enormous costs of armed conflict, the latter motivations are much more likely motives for armed conflict than the desire for financial gain.

- Due to their monopolistic positions, governments can afford to make extremely large and costly errors without fear of being supplanted. For example, the estimated combined cost of the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan is $2.4 trillion,[10] and yet the U.S. government need fear no loss of market share as a result of this dubious investment. If each American could choose between a government that carried on these wars and one that did not and if each individual were guaranteed to actually get what he chose, then even the most ardent hawks might find themselves thinking twice about the price tag. Fortunately for the government, individuals have no such choice.

- Governments have better propagandistic tools at their disposal than private businesses. Since most people believe in political authority, the state can claim that citizens are morally obligated to go to war, whether they support the war or not. The state may portray combat under its command as 'fighting for one's country', which is generally seen as noble and honorable. A private business seeking to increase profits by killing competitors would have a harder sell.

- Human beings are far more willing to kill those who are perceived as very different from themselves, especially foreigners, than to kill ordinary members of their own society.[11] Consequently, it is easier to convince people to go to war against another country than it would be to convince people to attack employees of another company.

- Modern military training employs techniques of intensive psychological conditioning and desensitization to overcome soldiers' humane instincts. The U.S. military adopted techniques of this kind in response to Marshall's findings concerning the low rate of firing by World War II soldiers. As a result, the rate of fire reportedly increased from under 25 per cent in World War II to 55 per cent in the Korean War and close to 90 per cent in the Vietnam War.[12] Employees of a security company, however, are less likely to submit to military-style conditioning, since they would not see the need of combat with other security agencies to begin with.

- Due to its pervasive control over the society from which its soldiers are drawn, the state can and does apply powerful sanctions to soldiers who refuse to fight or citizens who refuse to be drafted. Under a governmental system, those who refuse to fight at their government's command must flee the country to avoid imprisonment or execution;[13] under an anarchist system, those who refuse to fight at their employer's command must merely find another job.

- Because of their monopolistic position and their ability to collect nonvoluntary payments from the populace, governments tend to have far greater resources than nongovernmental organizations, enabling them to accumulate vast arsenals even during peacetime. For example, as of this writing, the U.S. government maintains ten Nimitz-class aircraft carriers, which cost $4.5 billion apiece plus $240 million per year for maintenance[14] while generating zero revenue. As a result, when war breaks out between governments, it is far more destructive than any kind of conflict involving any other agents. The death toll from war in the twentieth century is estimated in the neighborhood of 140 million,[15] and the problem may yet prove the cause of the extinction of the human species.

Taking all of these observations into account, then, it appears that warfare is a greater concern with governments than with protection agencies.

10.4 Protection for criminals

I have described a system of private agencies devoted to protecting individuals from crime; that is, from theft, physical aggression, and other rights violations. But why should there not be agencies devoted to protecting criminals from their victims' attempts to secure justice? What asymmetry between criminals and peaceful cooperators makes it more feasible, profitable, or otherwise attractive for an agency to protect ordinary people than to protect criminals?

10.4.1 The profitability of enforcing rights

There are at least three important asymmetries that favor the protection of noncriminal persons over criminals. First, far more people wish to be protected against crime than wish to be protected in committing crimes. Almost no one desires to be a crime victim, while only a few desire to be criminals. Second, the harms suffered by victims of crime are typically far greater than the benefits enjoyed by those who commit crimes. Ordinary people would therefore be willing to pay more to avoid being victimized than criminals would be willing to pay for the chance to victimize others. In virtue of these first two conditions, there is far more money to be made in the business of protection against criminals than in the business of protection for criminals. Given that the two 'products' exclude each other - if one product is effectively supplied in the marketplace, then the other necessarily is not - it is the less profitable one that will fail to be supplied. If a rogue protection agency decides to buck the trend by supporting criminals, it will find itself locked in perpetual and hopeless conflict with far more profitable and numerous protection agencies financed by noncriminal customers.

The third asymmetry is that criminals choose to commit crimes, whereas crime victims do not choose to be victimized. Criminals, in other words, intentionally engage in behavior guaranteed to bring them into conflict with others. From the standpoint of a protection agency, this is an unattractive feature in a client, since the more conflicts there are in which the agency is called upon to protect clients, the higher the agency's costs will be. Ordinary, noncriminal clients are aligned with the agency's goals in this respect: they do not wish to be involved in conflicts any more than the agency wishes them to be. Criminal clients are a very different story. Offering protection for criminals is analogous to offering fire insurance for arsonists.

10.4.2 Criminal protection by governments

What about the analogous problem for governments: are there forces that prevent a government from acting to protect criminals?

Governments commonly act to protect society against those who violate others' rights, such as common murderers, thieves, rapists, and so on. On the other hand, during the slavery era, government protected slave owners from their slaves rather than the other way around. Before the civil rights movement in the United States, government enforced racial segregation. And today, democratic governments function as tools for special-interest groups to steal from the rest of society.[16]

These examples show that both patterns are possible: government can protect people's rights, and it can also protect rights violators. The question is whether the unjust pattern of protecting rights violators would be more common for a protection agency than for a government. Governments and protection agencies are both human organizations, staffed by agents with human motivations. To assume that governments are altruistically motivated while protection agencies are selfishly motivated is to apply a double standard designed to skew the evaluation in favor of government.

If we avoid such double standards, it is hard to see why governments should be thought less prone to protect rights violators than private agencies would be. One could argue that democratic governments must respond to the desires of voters, most of whom are opposed to crime. But one could equally well argue that protection agencies must respond to the desires of consumers, most of whom are opposed to crime, and there are reasons for expecting the market mechanism to be more responsive than the democratic mechanism (see Sections 10.7 and 9.4).

10.5 Justice for sale

Some object to free market provision of protective services on the grounds that justice should not be bought and sold. On the surface, this objection skirts uncomfortably close to a bare denial of the anarcho-capitalist position. To avoid begging the question, the objector must articulate a specific reason why protection and dispute resolution services should not be bought and sold. Two initially plausible reasons might be offered.

10.5.1 Preexisting entitlement

One argument is that people should not have to pay for justice, because everyone is entitled to justice to begin with. Just as I should not have to pay for my own car (again) once I already own it, I should not have to pay for anything else to which I am already entitled.

In one sense, this is correct - no one should have to pay for justice. But what the objection points to is, not a flaw in the anarcho-capitalist system, but a flaw in human nature, for the necessity of paying for justice is created, not by the anarcho- capitalist system, but simply by the fact that criminals exist, and that fact has its roots in the perennial infirmities of human nature. In an idealistic, utopian sense, we can say that everyone should simply voluntarily respect each other's rights so that no one need ever pay for protection.

Given, however, that some people do not in fact respect others' rights, the best solution is for some members of society to provide protection to others. This costs money, and there are at least two reasons why the protectors cannot be asked simply to shoulder the costs themselves. First, there is the practical argument that few people are willing to expend their time and resources, to say nothing of the physical risks undertaken by security providers, without receiving some personal benefit in return. If we decide that it is wrong to charge money for a vital service such as rights protection, whereas one can charge whatever one likes for inessential goods such as Twinkies and cell phones, then we will build a society with plenty of Twinkies, cell phones, and rights violations.

Second, those who provide protective services are justly entitled to ask for compensation for their time, their material expenses, and the physical risks they undertake, at least as much as anyone else who provides services of value to others. It would be unjust to demand that they bear all these burdens while their beneficiaries, those whom they protect, may simply proceed with their own self-serving occupations, bearing none of the costs of their own defense. If anything, the vital importance of the protection of rights entitles those who provide this service to ask for greater rewards than those who provide less essential goods and services.

10.5.2 Basing law on justice

Another reason for thinking that protection from crime should not be subject to market forces is that this is incompatible with the laws' being determined, as they ought to be, by what is morally right and just.

Again, there is something obviously correct in this thought: human beings should respect moral principles, and they should design social rules to promote justice and ethical behavior. But this is no objection to anarcho-capitalism. In adverting to self-interest to explain how security agencies in an anarchist society would behave, I am not advocating selfishness; I am recognizing it as an aspect of human nature which exists regardless of what social system we occupy. One can design social institutions on the assumption that people are unselfish, but this will not cause people to be unselfish; it will simply cause those institutions to fail.

This is not to say that people are entirely selfish. Insofar as human beings are moved by ideals of justice and morality, these motives would only strengthen the rights-protecting institutions of the anarchic society. The ethically proper job of a protection agency is to protect the rights of its customers, and in the case of disagreement, to enforce the decisions of an arbitrator. The proper job of an arbitrator is to find the fairest, wisest, and most just resolutions possible of the disputes placed before him. The faithful discharge of these duties is not precluded by the fact that the agencies and the arbitrators have self-interested reasons to do these things.

10.5.3 Buying justice from government

The preceding objections in any case cannot favor government over anarchy, because government is subject to the very same objections. In a government-dominated system, people must pay for justice, just as surely as in an anarchist system. It is not as though courts and police forces can somehow operate without cost if only they are monopolistic and coercive. If anything, the monopolistic and coercive aspects of government justice systems make them more expensive than a competitive, voluntaristic system. The difference is simply that in governmental systems, payments are collected coercively under the name of 'taxation', and provision of the service is not guaranteed even if you pay.[17] Presumably, these differences do not render the system more just.

Likewise, the laws enforced by a government are no more determined by justice and morality than those enforced by private protection agencies and arbitration firms. In a representative democracy, the laws are determined by the decisions of elected officials and the bureaucrats they appoint. Election outcomes, in turn, are affected by such factors as charisma, physical attractiveness, campaign funding, name recognition, the skill and ruthlessness of campaign managers, and voter prejudices.

Some say that politicians and bureaucrats are supposed to serve impartial ethical values, whereas business managers are only supposed to generate profits for their business. What does this mean? Who supposes that public officials are motivated in this way, and what difference does such supposition make? One argument is that because there is a general socially accepted norm to the effect that public officials should serve justice, public officials will themselves feel more inclined to behave in that way than they would in the absence of such a norm. In contrast, since no such norm is generally accepted in the case of businesses, business managers will feel little sense of obligation to serve justice.

There are two natural replies to this argument. The first is to question the relative importance of moral motivation, emphasizing instead the practical value of aligning agents' self-interest with the requirements of justice. Granted, the ideal system is one in which people serve justice for the right reasons. But for the reasons explained in Chapter 9, government is unlikely to be that system. If one must choose between a system in which people serve self-interest in the name of justice and one in which people serve justice in the name of self-interest, surely we must prefer the latter. To prefer a system that hands people the tools to exploit others for selfish ends while assuring them that they are supposed to serve justice, over a system that makes justice profitable and allows people to choose their course, would be to repose a utopian faith in the power of supposition.

The second reply is that there is no reason why the members of an anarchy may not embrace equally idealistic norms as those of a democratic society. Just as citizens of a democratic state believe that public officials should promote justice, the members of an anarchy may hold that protection agencies and arbitration firms should promote justice. However much efficacy that kind of social norm has in policing human behavior, the anarchist may harness it just as well as the statist.

10.6 Security for the poor

Another concern is that security agencies, driven by the profit motive, will cater solely to the rich, leaving the poor defenseless against criminals.

10.6.1 Do businesses serve the poor?

Unfortunately, there are no actual societies with a free market in security. We can, however, examine societies with relatively free markets in a variety of other goods and services. In such societies, for how many of these other goods and services is it true that suppliers cater solely to the rich, providing no products suitable for middle-and lower-income customers? Is clothing manufactured solely for the wealthy, leaving the poor to wander the streets naked? Do supermarkets stock only caviar and Dom Perignon? Which chain is larger: Walmart or Bloomingdale's? Admittedly, there are some products, such as yachts and Learjets, that have yet to appear in affordable models for the average consumer, yet the overwhelming majority of industries are dominated by production for lower-and middle-income consumers. The main explanation is volume: for most products, there are many more consumers seeking a cheap product than consumers seeking an expensive product.

The wealthy, of course, tend to receive higher quality products than the poor, from food to clothing to automobiles (that is the point of being wealthy). Under anarchy, they would no doubt receive higher-quality protection as well. Is there an injustice in this?

In one sense, yes: as a result of imperfect protection, some poor people will become victims of crime. This is unjust, in the sense that it is unjust that anyone ever suffers from crime. The injustice inherent in crime, however, points to a flaw in human nature rather than in the anarchist system. Some people will suffer from crime under any feasible social system. The question is whether anarchy faces a greater problem or a greater injustice than governmental systems.

One might think that anarchy will suffer from a further injustice beyond simply the existence of crime; namely, the inequality in the distribution of crime, the fact that the poor are subject to greater risks of crime than the wealthy. In my view, this is not an additional injustice over and above the fact that people suffer from crime. In other words, given a fixed quantity of crime, as measured perhaps by the number and seriousness of rights violations occurring in a society, I do not believe that it matters, ethically, how the crime is distributed across economic classes. Questions in this vicinity, however, are beyond the scope of this book.[18]

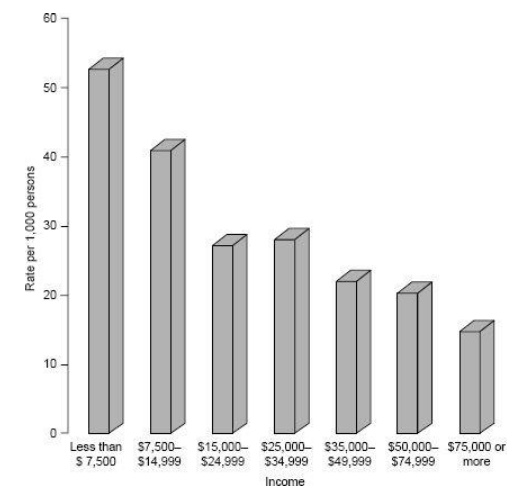

Figure 10.1 Frequency of crime victimization by income

10.6.2 How well does government protect the poor?

Even if inequality in the distribution of crime is an independent injustice, this does not obviously favor government over anarchy, since large inequalities in the distribution of crime occur in all state-based societies as well, where the wealthy are much better protected than the poor. To take a contemporary example, Americans with incomes below $7500 per year are three and a half times more likely to suffer personal crimes than those with incomes over $75,000 (see Figure 10.1), despite that the wealthy might initially seem a more attractive target for most crimes.[19] Though this is not the only possible explanation, it is plausible to hold that this inequality is at least partly due to inadequate protection offered by the state to the poor. Whether an anarchist system would have more or less inequality in the distribution of crime remains a matter for speculation.

10.7 The quality of protection

How well would private protection agencies protect their clients, in comparison with police under the status quo? This comparison is difficult to make since we cannot observe an anarchist society. The best we can do is to examine the effectiveness of government police and then make theoretical predictions about the anarchist alternative on the basis of the incentive structures.

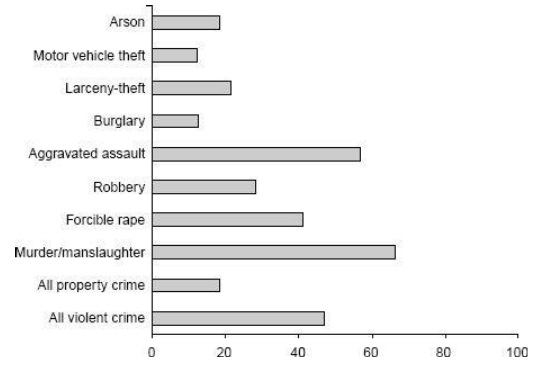

The status quo leaves considerable room for improvement. We do not know how many people are deterred from a life of crime by the prospect of being punished by the state, but we have a fair idea of how often those who turn to a life of crime are in fact punished. According to FBI statistics, only about half of all reported violent crimes and a fifth of reported property crimes are solved by law enforcement agencies (see Figure 10.2).[20] These figures actually give an overestimate of the effectiveness of government law enforcement since they do not account for unreported crimes.

On a theoretical level, it is not difficult to understand why government police might be less effective than private protection agencies. If a protection agency provides poor protection or charges excessive fees, it must fear loss of customers to rival agencies. But if the police provide poor protection at a high price, they need have no fear of losing market share or going out of business. Since they have monopolized the industry, the customers have nowhere else to turn, and since their revenue derives from taxation, the customers cannot decide to fire their protectors and fend for themselves. These enviable features of the state's position enable it to survive indefinitely almost irrespective of its performance. Indeed, the poor performance of police is more likely to bring them financial rewards than to bring financial losses, since rising crime rates tend to cause increases in law enforcement budgets rather than cuts (compare Section 9.4.7). Private protection agencies, lacking these advantages, would have no recourse but to provide sufficient protection to their customers at a reasonable price.

Figure 10.2 Percentage of U.S. crimes cleared by arrest

10.8 Organized crime

Private protection agencies might be able to deal with the common criminal, but how would they deal with organized crime? Do we not need a central authority to combat this problem?

Government has extensive programs for fighting organized crime; they focus almost entirely on direct enforcement efforts - that is, efforts to arrest and prosecute criminals, particularly the criminal leadership. But doubts have been raised about the effectiveness of this approach.[21] Evidence of the effect of these enforcement efforts on overall crime levels is lacking, and it may well be that the roles occupied by jailed crime bosses are simply filled by other criminals, resulting in negligible benefits to society in terms of total crime.[22]

Aplausible alternative approach would be to attempt to deny organized crime its most important sources of revenue.

Criminal organizations are chiefly focused on collecting money, which they do mostly through the provision of illegal goods and services. Traditionally, organized crime has generated revenue for itself through gambling operations, prostitution, and (during the Prohibition era in the United States) the illegal sale of alcohol. By far the main source of revenue for organized crime today appears to be the illicit drug trade, which is estimated to generate between $500 billion and $900 billion in sales worldwide per year.[23]

Why have criminal organizations focused on these industries? Why sell gambling services, sexual services, and drugs rather than, say, shoes and chocolates? There is no controversy about the answer to this: it is because gambling (in some forms), prostitution, and narcotic drugs are illegal. Al Capone made his fortune selling alcohol, not when it was legal, but during the era of Prohibition. Today, organized criminals make their fortune selling marijuana and cocaine rather than penicillin and Prozac. The reason is that criminals have no advantages in the provision of ordinary goods and services; their only special asset is their willingness and skill in defying the law. Unlike ordinary businesspeople, criminal individuals are willing to risk imprisonment for the sake of money; they are willing to forgo all social respectability; and they are willing to engage in bribery, threats, and violence to pursue their business. These are the traits needed to supply a good that is illegal. By prohibiting certain drugs, we grant control of the recreational drug industry to people with those characteristics. If these same drugs were legalized, the criminals now making fortunes from their sale would no longer be able to do so because they would no longer have any economic advantage in that industry. This is the lesson of Capone and Prohibition.

Thus, a powerful strategy for crippling organized crime would be to legalize drugs, gambling, and prostitution. I do not claim that this would eliminate all organized crime. It would, however, strike a blow to organized crime more devastating than anything the state could hope to do by way of wiretaps, sting operations, and indictments. The vast majority of organized crime's revenue stream would dry up virtually overnight, forcing most of its members to seek other employment.

In an anarchist society, it is highly probable that drugs, gambling, and prostitution would all be legal. The essential difference between these 'crimes' and more paradigmatic crimes such as murder, robbery, and rape is that the latter crimes have victims, whereas gambling, drug use, and prostitution have no victims - or at any rate, no victims who are likely to complain.[24] In the anarcho-capitalist society, rights are enforced by the victim of a rights violation bringing a complaint against the rights violator through his protection agency and relying upon a private arbitrator to judge the validity of the complaint. There is no effective mechanism for prohibiting victimless crimes, because there is no legislature to write the statutes and no public prosecutor to enforce them.

What if a large number of people were so strongly opposed to prostitution that they were willing to pay their protection agencies to 'protect' them from living in a society in which other people buy and sell sexual services? And what if arbitrators in this society agreed that anyone complaining about someone else's trade in sexual services had in fact been wronged (perhaps through being offended) and was entitled to compensation by either the prostitute or the prostitute's client? In theory, a society of this kind could end up with antilibertarian prohibitions on prostitution; however, this is an improbable scenario, since few people in fact think that a contract to purchase sexual services victimizes any person who merely finds out about it and doesn't like it, and few are in fact willing to pay as much to prevent other people from engaging in prostitution as prostitutes and their clients are willing to pay to be left alone. Similar observations apply to other victimless crimes, such as gambling and recreational drug use.

This does not eliminate all possible revenue sources for organized crime; criminals could still collect money, for example, through extortion and fraud. Nevertheless, denied their largest sources of revenue, criminal organizations would be much weaker in an anarchist society than they are today and would probably play a very small role.

10.9 Protection or extortion?

Rather than providing protection in exchange for agreed-upon fees, it might seem that it would be more profitable for a 'protection' agency simply to rob people without bothering about protecting them. Why wouldn't protection agencies evolve into mere extortion agencies?

10.9.1 The discipline of competition

Interagency competition is the main force restraining abusive practices by protection agencies. Customers would subscribe to the agency that they expected to serve them best at the lowest cost, without robbing, abusing, or enslaving them.

Imagine two protection agencies operating in the same city, Tannahelp Inc. and Murbard Ltd.[25] Tannahelp is a legitimate agency that enters into voluntary agreements with its customers, providing protection in exchange for a fee. Murbard is a rogue agency that extorts money from people while providing little of value in return. Almost anyone would prefer Tannahelp, and therefore, if individuals could freely choose their protection agency, Murbard would quickly go out of business. If Murbard tried to force people to join it instead of Tannahelp, people would appeal to Tannahelp for protection.

We saw above the incentives that oppose violent conflict between agencies. Tannahelp might therefore attempt to resolve the dispute with Murbard through third-party arbitration. Murbard could accept the offer of arbitration, in which case any fair judge would rule against it; it could abandon its extortionist plan, or it could prepare for war.

There are four reasons why Murbard would be more likely to either back down or be destroyed than Tannahelp. First, Tannahelp would be perceived as more legitimate than Murbard by the rest of society. Tannahelp would therefore have a much better chance of convincing employees to fight on its behalf than Murbard, though it might be that neither agency would succeed and that employees on both sides would desert rather than fight.

Second, Tannahelp would have the support of all the customers over whom the agencies were fighting. The customers would therefore be likely to attempt to assist their favored agency and hinder the extortionist agency.

Third, Tannahelp would have more reason to fight than the criminal agency. If Tannahelp allows some of its would-be customers to be enslaved to a criminal agency, it establishes a precedent that will likely ultimately lead to its own demise. Murbard, on the other hand, could at any time desist from its extortionist plans and decide to run a legitimate business protecting people from criminals. We have seen earlier the reasons why violent conflict would be very harmful for both agencies. Since both agencies are aware of this and both also know that it is Murbard that can better afford to back down, that is what will most likely occur.[26]

Fourth, the rest of society, including the other protection agencies in the area, would side with Tannahelp. This is partly due to common sense ethical beliefs - almost everyone considers extortion to be unjust - and partly due to self-preservation - if Murbard triumphs against Tannahelp, Murbard will probably next move on to the customers of other agencies. Other agencies are thus likely to assist Tannahelp enough to ensure its victory, even if they allow Tannahelp to do most of the work.

The preceding scenario supposes that Murbard starts out as an extortionist agency and tries to steal customers of other agencies or to force unaffiliated customers to join Murbard. What if Murbard starts out as a legitimate agency, acquiring customers through voluntary agreements, and only later evolves into an extortionist agency that prohibits existing customers from leaving?

In this case, it seems less likely that Tannahelp would fight a war to free Murbard's existing customers. Nevertheless, there are three factors that would limit the damage potential of this type of scenario. First, any such transition is unlikely to occur suddenly and without warning. Because the sorts of people who tend to be attracted to legitimate, service-providing businesses are different from those who are attracted to mafia-like crime rings, the transition from the former to the latter would most likely involve a change of personnel, both at the management level and at the level of average workers. Perhaps a criminally minded person somehow gets into a management position, where he starts making changes, expelling existing personnel and hiring friends and family members with criminal leanings. While this transition was taking place, customers who did not like the direction in which the company was moving would leave the company in favor of competing agencies. The resulting drop in company profits would probably cause the company to stop what it was doing. If not, most of the customers would probably have left by the time the process was complete.

Second, the most credible version of the scenario would have the extortionist agency controlling one or more small geographical areas, such as individual neighborhoods whose homeowners' associations had originally signed on with the agency voluntarily. If, however, the agency's behavior was sufficiently egregious, customers would prefer to leave the neighborhood rather than continue being subject to extortion. Assuming that there were many other protection agencies in the society serving otherwise similar neighborhoods, it would be extremely difficult for Murbard to keep its victims from leaving.

A similar observation could be made about governments: if one country's government is sufficiently tyrannical, corrupt, or otherwise objectionable, citizens may leave the country. Note, however, that the mechanism of exit is more effective on the neighborhood level than it is on the national level. Individuals who flee their native country are generally forced to leave behind their culture, their jobs, and their family and friends. In contrast, those who merely relocate to a different neighborhood within the same society can generally retain their culture, job, family, and friends. Furthermore, other nations typically impose severe barriers to immigration, whereas other neighborhoods within the same society generally do not. As a result, a national government can be much more abusive before it loses most of its citizens than can an organization limited to a single neighborhood.

Finally, even if Murbard holds onto some of its original customers, it is unlikely to acquire any new customers. As a result, Murbard's customer base will slowly dwindle, while other agencies that better serve their customers expand. This is likely to serve as an example to companies considering making the transition to extortion rings in the future.

10.9.2 Extortion by government

Now consider the analogous problem for governmental systems: why shouldn't the government extort money from people without protecting them? All governments in fact extort money, though the practice is usually termed 'taxation' rather than 'extortion'. Few statists even contemplate ending this practice. How, then, might government be thought superior to anarchy in this area?

Perhaps one might think that government takes less of our money than private protectors would charge or that government provides better service than private protectors would provide. But it is difficult to see why this would be so. Imagine that a private protection agency somehow acquired a monopoly in a large geographical area and began to extract payments from the population by force. Few would contend that, once this state of affairs transpired, prices would drop and service would improve. Surely the opposite would occur. But that is precisely the position of societies with government-based protection. Perhaps it is the democratic process that is supposed to induce government to control costs and maintain high-quality service: if the government does a poor job, people will vote for different politicians. The question then becomes whether this mechanism is more or less effective than the mechanism of free market competition. One shortcoming of the democratic mechanism is that the choices tend to be very limited. In some democratic societies, elections regularly offer only two choices; for example, the Democrats and the Republicans in the United States. Even systems of proportional representation rarely give voters the range of options present in typical free markets.

But the more important shortcoming is that, in the democratic system, when one chooses one politician over another, one does not thereby get what one chooses; one gets what the majority chooses. Therefore, there is little incentive to expend effort on rational or informed voting (see Section 9.4.3).

10.10 Monopolization

Some believe that a free market anarchist system would evolve into a state, as one protection agency monopolized the industry. In the present system, nearly all monopolies and monopoly-like conditions are created by government intervention, usually prompted by special-interest groups seeking rents.[27] To endorse the objection from monopolization, therefore, we need some reason to believe that the protection industry would differ from most other industries in some way that would render it particularly prone to monopolization in the absence of state intervention.

10.10.1 The size advantage in combat

Robert Nozick contends that the protection industry would succumb to natural monopoly because the value of a company's service is determined by the relative power of that company in comparison with other companies.[28] Nozick imagines agencies doing battle to resolve disputes between customers. If one agency is more powerful than another, the more powerful agency will triumph. Recognizing that it is better to be protected by the stronger agency, the customers of weaker agencies will migrate to stronger agencies, making the latter even stronger. Since this sort of process tends to amplify initial differences in power, the natural end result is that one agency holds all the power; that is, a monopoly of the industry. Nozick goes on to explain how this dominant protection agency might develop into a full-fledged government.[29]

If the task for which one hires a protection agency were that of fighting other agencies, then Nozick's analysis would be correct. But one does not hire a protection agency to fight other agencies, nor would agencies provide that service (Section 10.3). One hires a protection agency to prevent criminals from victimizing one or to track down criminals after the fact. In this task, one's protection agency must have the power to apprehend criminals, but it need not have the power to defeat other protection agencies, given that other agencies are not in the business of protecting criminals (Section 10.4).

Nozick considers the possibility of agencies relying on third-party arbitration, which he assumes would occur only if two agencies were of approximately equal strength. Pace Nozick, the peaceful arbitration solution does not depend upon the assumption that agencies are of approximately equal strength nor that combat between them results in stalemate. It depends only upon the assumption that physical combat between agencies is more costly than arbitration, an assumption that is virtually guaranteed to hold in almost any conflict.

Nozick assumes that arbitration would lead to 'one unified federal judicial system' to which all would be subject.[30] He then proceeds, in his subsequent reasoning about the emergence of a state, to speak of the activities of 'the dominant protective association', leaving the reader perhaps to assume that a unified judicial system is equivalent to a dominant protection agency. He does not explain why the arbitration industry would be controlled by a monopoly nor why a monopoly of arbitration would be equivalent to a monopolistic protection agency.

10.10.2 Determining efficient size of firms

Under some conditions, a monopoly can develop naturally in a free market. If the most efficient size for a firm in a particular industry is so large that there is room for only one such firm in the marketplace, then the conditions are ripe for a natural monopoly.[31]

Large firms often benefit from economies of scale. For example, in the automobile industry, the lowest per-unit production costs are achieved by operating a type of factory that is capable of producing tens or hundreds of thousands of cars per year. Because there is a large fixed cost for building such a factory - a cost that must be borne to produce any cars at all but that does not increase as one builds more cars up to the maximum capacity of the factory - it is most economically efficient to use the factory to full capacity once built. Any firm trying to sell less than many thousands of cars per year is thus at a competitive disadvantage to larger firms - it will be forced to charge higher prices for its cars. Economies of scale, however, operate only up to a certain point - there is no greater efficiency involved in operating ten automobile factories than in operating one.

On the other hand, large firms also suffer from diseconomies of scale. Factors that tend to make a larger firm less efficient include bureaucratic insularity, alienation on the part of employees, increased costs of communication within the organization, and increased risk of duplication of effort within the organization.[32]

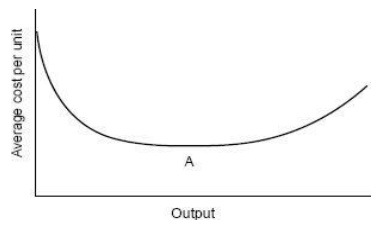

Because economies of scale cease to apply after a certain point and diseconomies of scale begin to apply at a certain point, there is a limit to how large an efficient firm can be (see Figure 10.3). This limit varies with the industry. In the automobile industry, the most efficient firms are very large because of the nature of automobile factories, which cost hundreds of millions of dollars. In industries with lower fixed costs, the most efficient firms will be smaller.

What about the protection industry? The fixed costs for a protection agency are minimal. The business owner must have sufficient funds to hire a few employees and equip them with weapons and tools for enforcement and investigation. No expensive factory, large land area, or large reserve of capital is required. There are no obvious significant economies of scale. It therefore appears that there is no economic pressure towards the formation of large firms in this industry, and the industry will most likely contain a very large number of small and medium-sized firms. Large firms would be at a disadvantage, as they would suffer from the usual diseconomies of scale without reaping significant compensatory economies of scale.

10.10.3 Government monopoly

As in the case of the previous objections, the threat of monopoly poses a more serious objection to government than to anarchy. We need not present arguments to show that a government may develop into a monopoly, because a government, by definition, already is a monopoly. Whatever ills are to be feared from the monopolization of industries, why should we not fear precisely those ills from government? The fact that an organization is labeled a 'government' rather than a 'business' will hardly render its actions beneficent if the actual incentive structure it faces is the same as that of a monopolistic business.

What is the problem with monopolies? Economic theory teaches that a monopoly will restrict output to socially suboptimal levels while raising prices to levels that maximize its own profits but lower the total utility of society. If, for example, a company held a monopoly on shoe production, there would be too few shoes, and they would be too expensive.[33]

That is the problem with a rationally self-interested monopolist. But matters are worse than this, because we cannot even assume that a monopolist will be rational. Competition makes firms act as something approximating rational profit maximizers by eliminating those who do not behave in that way. In the absence of competitive pressures, a firm has much more leeway. Optimists may observe that an organization with a robust monopoly can survive while magnanimously sacrificing profits for the good of society, if it happens to be so inclined. But it can also survive while clinging to inefficient production methods and resisting innovation; rewarding well-connected but incompetent people; wasting money on half-baked, ideologically motivated plans; ignoring evidence of customer dissatisfaction; and so on. To assume that monopoly privilege will be used only for good would seem to be an exercise in wishful thinking. Almost everyone accepts this in the case of nongovernmental monopolies; nothing essential changes when the label 'government' is applied to a monopolistic protection agency.

10.11 Collusion and cartelization

Apart from monopoly, there is a second anticompetitive practice that may increase the profits of firms in a given industry. This is the practice of forming a cartel, an association of firms that agree among themselves to hold prices at an artificially high level or otherwise cooperate to promote their mutual interests. As Adam Smith warned, 'People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.'[34] Some critics argue that the protection industry would fall under the dominance of a consortium of this kind, leading to results similar to those of an industry monopoly.

Figure 10.3 Average cost curve for a firm in an industry with both economies and diseconomies of scale.

Point A represents the most efficient size (the output level with lowest average cost)

10.11.1 The traditional problem for cartels

Most cartels have difficulty enforcing their policies. Suppose that the competitive market price for widgets is $100 per widget. The leaders in the widget industry, however, in a recent backroom meeting, have agreed that $200 is a much nicer price. One small firm, Sally's Widgets, demurs. While the cartel firms charge $200, Sally decides to charge only $150 per widget.[35] What happens?

At these prices, nearly all customers prefer a Sally widget over a cartel widget. Once a struggling small firm, Sally's Widgets suddenly can't expand fast enough for all the new customers approaching it. The cartel, tired of losing business, eventually abandons its scheme and competes with Sally on price but not before Sally's Widgets has enjoyed its greatest-ever boom in sales at the expense of the industry leaders. The incident stands as a lesson to players in other industries, where the smaller firms struggling to get established dream that, one day, the leaders in their industry, too, will devise a harebrained price-fixing scheme.

10.11.2 Cartelization by threat of force

Some industries may differ materially from the famously competitive widget industry. In those industries in which a firm's success depends upon its good relations with other firms, anticompetitive collusion may be more feasible because the large firms in the industry can effectively punish those who reject cartel policies. Tyler Cowen and Daniel Sutter suggest that this may be true in the protection industry because the success of a protection agency depends upon its ability to peacefully resolve disputes with other agencies.[36] Cowen and Sutter imagine the protection agencies in a given area forming a single multilateral agreement detailing the procedures for resolving disputes involving customers of different agencies. Having tackled that problem, the agencies might next agree to fix prices at artificially high levels and to refuse to cooperate with any new firms that may subsequently enter the market.

The agreement on procedures for arbitrating disputes would be self-enforcing, in the sense that firms choosing to violate it would be sabotaging themselves (Section 10.3). But who would enforce the anticompetitive agreements to fix prices and exclude new agencies? Cowen and Sutter imagine that the cartel excludes new entrants to the industry by refusing to accept arbitration with them; cartel members resolve any disputes with nonmembers through violence.[37] The same mechanism is used to enforce the price-fixing agreement: if any member company is found to have set prices too low, the remaining members expel the price-cutting agency and henceforth treat it like any other outsider, refusing arbitration in any future disputes with the ostracized agency.[38]

Although this seems to be a possible mechanism for taking over the industry, I do not find it very plausible that the mechanism would be employed. Suppose that agency A, which is a member of the cartel, has a dispute with agency B, which is not a member. A is supposed to be prepared to go to war with B rather than resolve the dispute peacefully. We have already seen that there are powerful motives for protection agencies to avoid violent confrontations, chiefly because (a) violent conflict is extremely costly and (b) most people have antimurder values. Therefore, for A to engage in armed conflict with B, A would have to be willing to sacrifice its own interests for the sake of maintaining the cartel.[39] Since the motivation for joining the cartel to begin with was one of economic self-interest, it is not plausible that A would make such a sacrifice.

Perhaps A might be moved to fight for the cartel by a further threat made by other cartel members: if A resolves its dispute with B peacefully, then other cartel members will henceforth go to war against A whenever they have a dispute with A. And what would motivate the other cartel members to do this? Well, the fact that if they don't, other members will go to war against them, and so on. This thinking, however, strikes me as a regress of increasing implausibility. If it was implausible that A would go to war against B for not being a member of the cartel, it is still less plausible that another agency, C, would go to war against A for not going to war against B for not being a member of the cartel. If A wishes to avoid armed conflict, its best bet would be to avoid the immediately looming conflict with B, perhaps doing its best to conceal its agreement with B from the other cartel members, and worry about possible future conflicts with other agencies later.

10.11.3 Cartelization through denial of extended protection

George Klosko proposes a different mechanism for cartelization of the protection industry.[40] He imagines a collection of gated communities, each served by a private security agency. Customers would desire 'extended protection'; that is, one would wish to be protected not only in one's own neighborhood but also when one left the neighborhood to go to work, visit friends, shop, and so on. To satisfy this demand, protection agencies would need to work together, developing common procedures and agreeing to protect each other's customers. But once the agencies had formed a consortium to provide extended protection, the consortium could easily evolve into a cartel designed to raise prices, limit competition, and so on. The cartel would limit competition by denying extended protection to the customers of nonmember agencies. Since almost everyone desires extended protection, nonmember agencies would be effectively excluded from the market. The cartel would enforce its policies internally by threatening to expel members who violate cartel policies.

How might this result be avoided? Let us begin by imagining a competitive, noncartelized protection industry, and consider whether extended protection is likely to be provided without the development of an industry cartel. Suppose, as Klosko does, that security agencies are hired by associations of property owners to protect particular areas (whether gated or not). This may include both residential and commercial areas.

Now suppose that a homeowners' association is deciding whom to hire for neighborhood security. Agency A offers to protect residents, and only residents, from crime occurring in the neighborhood. If one of their security guards witnesses a crime, he will first try somehow to check whether the victim is a resident or a visitor. If the victim appears to be a visitor, the guard will allow the crime to proceed. Agency B, on the other hand, offers to combat all crime in the neighborhood, whoever the victim may be. There are two evident reasons why A's offer will be rejected: first, homeowners are likely to perceive the idea of verifying the identity of a victim before acting to stop a crime as both impractical and immoral; second, most people would like to be able to have visitors to their neighborhood and would like those visitors to be safe while in the neighborhood. Agency B will therefore win the contract.

A similar point applies even more clearly to owners of commercial property. It takes no great altruism for a business owner to recognize that he had better provide a safe environment not just for himself but also for his customers and employees. If people other than the owner are frequently attacked or robbed while on company premises, it may be difficult to run the business. Therefore, businesses will pay protection agencies to protect everyone on their premises.

Thus, extended protection is provided with no need for industry-wide collusion. Each protection agency, acting independently, simply provides what its customers desire. If several agencies decide to form a consortium and announce that henceforth, they will only protect customers of member agencies, every agency in the consortium will quickly lose nearly all of its contracts.[41]

10.12 HOA versus government

I have imagined local homeowners' associations and associations of property owners generally hiring agencies to provide security in particular neighborhoods or business districts. Why would such associations exist in an anarchic society, and why do they not qualify as governments?

The developer of a housing complex creates a homeowners' association, which residents are required to join as a condition of buying a unit in that complex, with the understanding that membership in the association is attached to the property so that all subsequent owners are subject to the same condition. The developer creates this institution because it increases the value of the property; most potential buyers are willing to pay more for a unit in the complex knowing that everyone in the complex will be a member of the association than they would if there were no association or if only some residents were to be members of it.[42] This is because an association to which all belong can provide important goods, such as a set of uniform policies for residents or (particularly in an anarchist society) arrangements to prevent crime within the development. HOAs have spread rapidly in the United States since 1960 and now cover 55 million people.[43] In an anarchist society, they would probably be even more widespread.

Since HOAs can make rules for residents, which may be enforced through the HOA's security agency, it might be thought that an HOA amounts to a kind of government, albeit a very small, localized government, so that the system here envisioned is not anarchy after all.[44]

On the semantic question of whether an HOA qualifies as a small government, it is worth noting that these entities actually exist at present and some even hire their own security guards, yet they are not generally considered to be governments. It might be suggested that they would qualify as 'governments' but for the existence of other bodies with power over them; namely, the entities actually called 'governments'. This semantic question, however, is of no great import, and I am not concerned to dispute the position of one who wishes to describe my proposal as one of very small, decentralized government rather than anarchy. What is important, however, is to see how an HOAdiffers from the institutions traditionally called 'governments'. It seems to me that there are at least three important differences.

The first is that because of its small size, residents have a much greater chance of influencing the policies of their HOA than they have of influencing the policies of a national, provincial, or even a typical city government. For this reason, members are more likely to vote in a relatively rational and informed way in HOA elections, and HOAs are more likely to be responsive to their members' needs and desires than a national government.

Second, more apropos of the central themes of this book, an HOA has the consent of its members through an actual, literal contract, in contrast to the merely hypothetical or mythological social contract offered by traditional governments. This gives them a moral legitimacy that no traditional government can claim.

Third, competition among housing developments with different HOAs is much more meaningful than competition among traditional governments. Individuals who are dissatisfied with their HOA can sell their interest and relocate to another housing development. The costs of relocation are not trivial, but nor are they enormous. By contrast, the difficulties of relocating to an entirely new country are much greater, if one is even allowed to relocate at all.

As a result of these factors, competitive pressure between governments is close to nonexistent, and governments can therefore afford to be much less responsive to their citizens than a typical HOA is to its members.

10.13 Conclusion

All social systems are imperfect. In every society, people sometimes suffer from crime and injustice. In an anarchist society, this would remain true. The test of anarchism as a political ideal is whether it can reduce the quantity of injustice suffered relative to the best alternative system, which I take to be representative democracy. I have argued that a particular sort of anarchist system, one that employs a free market for the provision of security, holds the promise of a safer, more efficient, and more just society.

The radical nature of this proposal usually calls forth strong resistance: it is said that justice should not be for sale; that the agencies will be at constant war with one another; that they will serve criminals instead of their victims; that they will serve only the rich; that they won't be able to protect us as well as the government; that they will turn into extortion agencies; that a monopoly or cartel will evolve to exploit the customers. These objections fairly flood forth when students, professors, and educated laypeople are first introduced to the idea of nonstate protective services. But if we examine the proposal more carefully and at greater length, we see that none of these objections are well founded. Anarchists have well-reasoned accounts, grounded in economic theory and realistic premises about human psychology, of how an anarchist society would avoid each of the disasters that critics fear.

Most of the objections raised against anarchy in fact apply more clearly and forcefully to government. This fact is often overlooked because, when confronted with radical ideas, we tend to look only for objections to the new ideas rather than for objections to the status quo. For example, the most common objection to anarchism, the objection that protection agencies would go to war with one another, overlooks both the extreme costliness of combat and the strong opposition that most people feel to murdering other people. The very real threat of war between governments appears a much more serious concern than conflict between private security agencies.

Similarly, the common objection that the security industry will be monopolized lacks foundation. Once we abandon the notion of security agencies doing battle with one another, economic features of the industry, particularly the minimal fixed costs for a security company, should lead us to predict a great number of small firms rather than a single enormous firm. On the other hand, a governmental system is monopolistic by definition and should therefore be expected to suffer from the usual problems of monopolies.

The central advantages of the free market anarchist system over a governmental system are twofold: first, the anarchist system rests on voluntary cooperation and is therefore more just than a system that relies on coercion. Second, the anarchist system incorporates meaningful competition among providers of security, leading to higher quality and lower costs. As a result of these features of the system, individuals living in a free market anarchy could expect to enjoy greater freedom and greater security at a lower cost than those subject to the traditional system of coercive monopolization of the security industry.

Notes

1 This proposal derives from Rothbard (1978, chapter 12) and Friedman (1989, chapter 29).

2 Rand (1964, 112-13) refers to the system as 'competing governments' but then argues that it is really a form of anarchism; she appears to be under the misapprehension that the advocates of anarcho-capitalism themselves called the system 'competing governments'.

3 Compare Weber's well-known definition of government: 'The state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory' (1946, 78; emphasis in original).

4 This objection appears in Wellman (2005, 15-16) and Rand (1964, 113). Friedman (1989, 115-16) responds.

5 The theory that violent conflict is due to aggressive personalities rather than, say, to rational self-interest is evidenced by the fact that such conflict is an almost exclusively male phenomenon.

6 Grossman (1995, 1-39) provides an overview of the empirical evidence for this.

7 Marshall 1978, chapter 5. Others have questioned Marshall's statistics, which are probably guesswork (Chambers 2003), but the overall picture remains unaltered (Grossman 1995, 333, n. 1). Commenting on the problem faced by military leaders, Grossman (1995, 251) remarks, 'A firing rate of 15 to 20 percent among soldiers is like having a literacy rate of 15 to 20 percent among proofreaders.'

8 Dr. John, quoted in Grossman 1995, 14-15.

9 The phrase seems to derive from Sandburg (1990, 43; originally published 1936). The original phrase is 'Sometime they'll give a war and nobody will come.'

10 Reuters 2007a, reporting a Congressional Budget Office estimate of total costs through the year 2017. The estimated cost for Iraq alone is $1.9 trillion. Stiglitz and Bilmes (2008), however, put the cost for both wars at at least $3 trillion.

11 Zimbardo 2007, 307-13; Grossman 1995, 156-70.

12 Marshall 1978, 9; Grossman 1995, 249-61.

13 The U.S. Uniform Code of Military Justice, Article 85, allows for any penalty up to and including death for desertion during wartime (www.ucmj.us).

14 U.S. Navy 2009; Birkler et al. 1998, 75.

15 Leitenberg 2006, 9. Most of these are civilian deaths; military deaths were close to 36 million (Clodfelter 2002, 6).

16 For discussion, see Section 9.4.3.

17 U.S. courts have repeatedly ruled that police and other government agents are not obligated to protect individual citizens. See Warren v. District of Columbia (444 A.2d. 1, D.C. Ct. of Ap., 1981); Hartzler v. City of San Jose, 46 Cal.App. 3d 6 (1975); DeShaney v. Winnebago County Department of Social Services, 489 U.S. 189 (1989).

18 On egalitarianism, see my 2003 and forthcoming.

19 U.S. Department of Justice 2010a, table 14.

20 U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation 2010, table 25. The statistics in the text and figure refer to the percentage of offenses 'cleared by arrest or extraordinary means'. This requires law enforcement officers to have located a suspect whom they had sufficient evidence to charge and to have either arrested and turned over the suspect to the courts for prosecution or been prevented from doing so by circumstances outside their control, such as the death of the suspect or refusal of extradition.

21 Paoli and Fijnaut 2006, 326; Levi and Maguire 2004.

22 Levi and Maguire 2004, 401, 404-5.

23 Finckenauer 2009, 308.

24 Some claim that illegal drug use victimizes the drug user's family, spouse, or coworkers (Wilson 1990, 24). However, these alleged crime victims are unlikely to bring a court case against the drug user and unlikely to prevail in a complaint against either user or supplier.

25 These names are taken from Friedman (1989, 116-17), apparently based on modifications of the names of prominent libertarian authors.